While the national football team of Belgium

has reached the second round of the World Cup for the first time since 2002,

amidst a national frenzy never seen

before, the formation of a national Belgium government has again become a

highly challenging matter. Mr. Bart De Wever, the leader of the Flemish

nationalists and winner of the parliamentary elections of the 25th

of May, is about to hand over his resignation to king Philip today, as he has

failed in his task to lay the groundwork for the formation of a new government.

De Wevers

party, the NVA, gained six seats in the federal parliament in last elections,

whereas the second best winner, the communist PTB, won two. The latter seats

were lost by the Parti Socialiste (PS), the biggest party in French-speaking

Belgium, led by the outgoing prime minister Elio di Rupo. It now has 24 MP’s, whereas

De Wever has 33. Di Rupo’s party is the only one of the six in the outgoing

government that lost seats. The two liberals parties and the Flemish Christian

democrats gained one each.

Having been charged with ‘informing’ the King about

the prospects for a new government on the 27th of May, the

nationalist leader has been working on a centre-right coalition since then. He

wanted, in his own words before the election, make a government without the

socialists for the first time in 25 years. To do so he needed to lure the

French-speaking liberals and Christian democrats into talks. Although it is no legal

obligation nor a fix tradition to have a majority in each language group, both

parties together have only 28 of the 63 seats for French-speaking parties.

But the PS,

still the biggest party in both the Brussels and Wallonia regions, and with Mr.

di Rupo in front, announced on the 5th of June that it would

immediately form a ‘progressive’ coalition with the French-speaking Christian

democrats (CDH) in both regional governments. Since then, and especially in the

last week, it is obvious that the PS was

pressing the CDH to stay out of Mr. De Wevers would-be federal government. Today

the Christian democrats, regardless of the lobbying of their Flemish

counterparts, complied, when their president, Benoit Lutgen, announced live in

the evening newsshow of RTL that ‘there is no confidence’ between him and Mr.

De Wever. The latter now will have to hand in his resignation.

The key to understand these developments is that with

the announcement of the 5th of June, Mr. di Rupo gave priority to

the regional governments over the federal one. Although this move was probably

done because of the electoral defeat of the party, it is nevertheless logic.

Regional coalitions need two or three parties at most to agree, whereas on the

federal level federal it takes at least four (and usually more) parties to

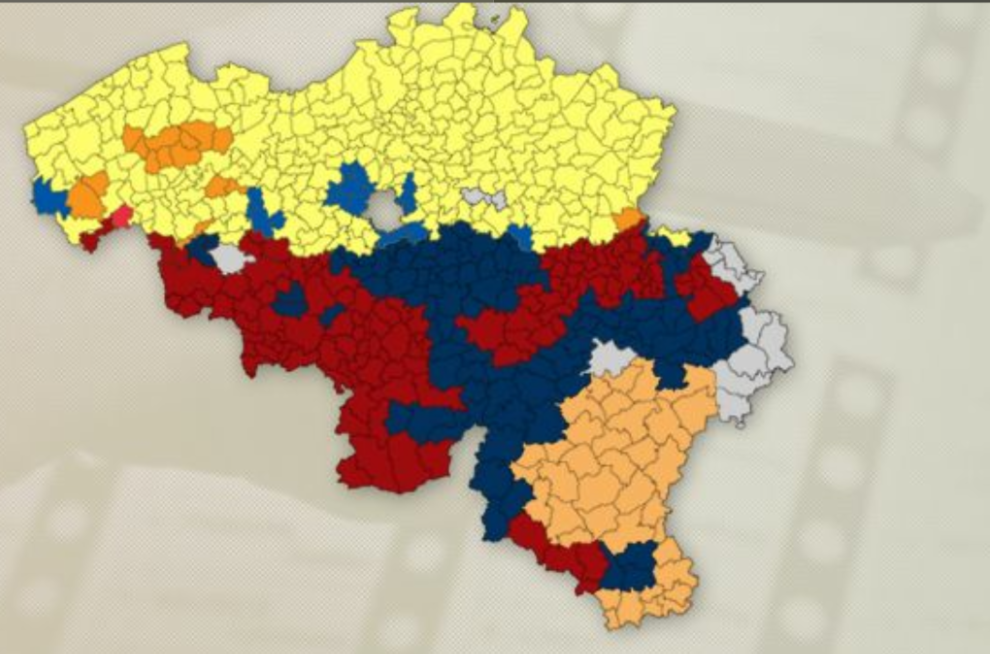

obtain a stable government. And as the electoral landscape in the north of the

country differs strongly from that in the south, it is not so easy to obtain

the same coalition in the federal and all regional governments.

The paradoxes in this new development since early June

are manifold. In the institutional reforms of the previous government of Mr. di

Rupo, regional and national elections were put on the same day again, to have

less elections with national impact – now on average every two years – and to

make the same coalition on all levels possible. The political pipedream was

that with at least four years without an election until the local polls at the

end of 2018, and with similar coalitions everywhere, the country would at last

be able to make some urgent social and economic reforms.

Mr. De Wever,

in opposition before the elections, heavily denounced this as an attempt to cut

the wings of the regional governments, especially the Flemish one. He announced

that the first thing he would do after victory was to form a centre-right

coalition in Flanders region to influence the formation of the federal

government. For this he was denounced by the PS as a separatist. After the

elections both Mr. De Wever and Mr. di Rupo have made a complete turnaround.

Lured into federal responsibilities by the king and his Flemish Christian democrat

friends, Mr. De Wever forgot about his threat, whereas Mr. di Rupo, beleaguered

by the forces of defeat, put it into practice.

Mr. Paul Magnette, the acting president of the PS as

long as Mr. di Rupo is prime minister, last week proposed to give up the idea

that regional and federal elections should be held on the same day. Again this

is both a logic conclusion of the latest events, and totally the opposite of

what he and his party defended before the elections. Such a reform is quite

feasible in the next years, but would probably be the first step towards a new

round of institutional reforms that everybody before the elections – except for

the NVA – wanted to avoid.

Regardless of

the bitter emotions these betrayals have instigated, they point to the same

unmistakable fact: both the PS and the NVA use their leading position in each

of the two communities in Belgium as a stronghold from which they (might) start

their conquest of the federal government. And keep the other one out: in this

first phase of probably long negotiations, Mr. De Wever has put a veto in all

but name on a federal coalition with the PS. In an interview last Thursday Mr.

di Rupo did the same, by saying that no decent party of the French-speaking

part of Belgium can enter into a coalition with the separatists of the NVA.

The federal government has become a battlefield of

nationalist perceptions: if it will be centre-left, this will be perceived as a

defeat for Flanders; if it turns centre-right, it will be pictured as bad for

French-speaking Belgium. Such is the cleavage between the global electorates in

the north and the south of the country – Mr. De Wever talks of ‘conflicting

democracies inside one country’ – that most of the possible coalitions in the

federal government could be perceived as the defeat of one community.

Could a new coalition of the three traditional

parties, like in the outgoing government, be presented as the moderate centre,

neither left nor right? Probably not anymore. Mr. De Wever build his latest

electoral victory in Flanders on precisely the image that this government was too

leftist and going against the interests of Flanders. After his blatant failure

to lure French-speaking parties into a federal government, he will make this

point stronger than ever. As for the PS, it is, after its losses against the

extreme left, probably no longer prepared to make the same concessions to some

centre-right wishes of the Flemish electorate as Mr. di Rupo did in his first

term.

In the Netherlands in 2012 the strongest opponents –

the liberals and the socialists – also won the elections by polarising the

electorate. They decided almost on the evening of the elections to be pragmatic

and to build a coalition of both, as

there was no alternative. Due to the nationalistic polarisation inside Belgium,

which adds to the one between left and right, this is far less evident. But even

if NVA and PS would find a compromise, it would probably be built on very

limited ambitions.

Obviously the most logic solution for every neutral

observer is that, when you have such different electorates and parties in each

part of the country and they are no longer capable of making compromises with

each other after elections, due to the pressure of voters and media, then you

have to decentralise the country as far as is thinkable. Almost as far as

Switzerland, leaving to the centre only the competence on which everybody

agrees that they cannot be assigned to the lower government levels. The problem with this scenario is that

French-speaking Belgium refuses it.

Due to the long economic decline of Wallonia in the

second half of the 20th century, the south of Belgium still has a long way to go before it can on its own

produce the level of prosperity of the north. Up to now it can, via the federal

government, tap into the economic benefits of Flanders to pay, among other

things, a generous and large unemployment bill and the cost of a quite a

generous social security in general.

But for Flanders, that has run into economic troubles

itself since about a decade, it is less and less acceptable to be refused a

centre-right government that could lower the record tax rates, temper the still

fast rising costs of social security or reduce the surplus in average wage cost

in industry compared to the neighbouring countries. Saying no to the winner of the elections, to centre-right

(after 25 years of centre-left) and to further devolution at the same time, is

probably the shortest way to make separatism in Flanders the most reasonable

alternative. Implicitly, already a third of the electorate is in favour. That

is already a huge number to keep stability in a country structure.

In the end the

impossibility to bring on a new federal government might generate creative

solutions. In the nineteen eighties, the first regional governments were coalitions

that reflected the proportional division of power between the parties in the

regional parliaments. If this should be applied today to the federal government

(always composed of seven Flemish and seven French-speaking ministers) you

would have a coalition of the three traditional parties in both communities,

with the NVA. The latter would also deliver the prime minister. Such

stabilising and face-saving scenarios are not unthinkable, but they show as

much that the normal democratic process in the formation of a Belgian

government is deeply disturbed.

For the moment Belgium seems again on its way to a record-breaking

long negotiation for a new government, with a new institutional imbroglio is in

the cards. The idea that the next four years could at last be the big

opportunity to pursue much-need reforms in the country is now indeed only a

pipedream. On the contrary, the growing political complexities of this small

and often successful country, are now rapidly weakening it, with the ghost of

separatism closing in fast.