Coalition talks for regional and the national governments are underway

in Belgium, with the negotiations on the federal government again in the slow

lane. There Mr. Bart De Wever, the 'informateur', is still seeking to form a centre-right

coalition without socialists, something not seen in Belgium since 1987. The

good news is that no one is breaking the confidentiality of the talks yet.

Mr. De Wever,

the leader of the Flemish nationalist and since the 27th of May 'infomateur' of

king Philipp to create a new federal government, is not so fond of football, it

is said. So he remained undisturbed by the bigger-than-ever frenzy in the

country around the national football team (with half of the players competing

in Englands Premier League). On Tuesday, when the so called Red Devils won

their first match on a World Championship in 12 years (2-1 against

Algeria), De Wever was briefing his

party council - Flemish nationalists,

but many nevertheless keen to see the match - about his weekly meeting

with king Philipp and the work ahead.

For the second

time in a row the king had given De Wever a week extra to finish what had twice

been announced as his final report. That is a sign that the winner of the

elections is still making progress - albeit a very slow one – in his attempt to

bring his party, both christian democrats, and the French-speaking liberals of

the MR around the table to form a new coalition.

Real formal negatiations are still far ahead, because

of the scepticism of all French-speaking parties about the real aims of the

Flemish nationalists – do they want to break-up Belgium or not? - and because the French-speaking Christian

democrats of the CDH already decided to link with the socialists in the

negotiations for the regional governments in Wallonia and Brussels. To soften

some of the suspicions, De Wever seems to have made a vague note on

socio-economic reform, but with one element undoubtedly absent: a demand for

further devolution

Flemish

newsmedia tend to believe that the Parti Socialiste, the biggest

French-speaking party and during the election campaign De Wevers favourite

target, is no longer interested in the federal government. The socialists, so

goes the story, fear new budget cuts like the ones that have already undermined

their position against the far left in their strongholds of Liège and Hainaut

during the government of Mr. di Rupo.

More likely a

power struggle is underway in the party, with generations at stake more than

ideologies, as the position of Mr. di Rupo, since 1999 its leader, seems no

longer secure. In that context it could

be a wrong assumption that the PS is going to give its junior coalition

partner, the CDH, the freedom to form a right wing federal government against

the … PS. French-speaking media at least do not believe in it.

There is still some talk of an alternative federal

centre-right government, with three Flemish parties – NVA, CD&V and the

liberal VLD – and only one French-speaking, the liberal MR. Due to the constitutional

obligation of having as much Flemish as French-speaking ministers in each

federal government, this could give the MR a lavish number of seven ministers

(in a group of 18 MP’s). But alone in a federal coalition, together with the

despised Flemish nationalists, and with 35 other French-speaking MP’s in the

federal parliament in opposition, this scenario looks also very much as

political hara-kiri.

The logic now

is that CDH will at least wait until it has a firm agreement with the PS in the

regional governments. Even then it will – at least in the perception - not be

so easy to betray its new partner by keeping him out of a new federal

government. This is the logic of

confederalism: the regional governments are first formed and this process influences

what happens with the federal one.

The conclusion

of regional coalition agreements is expected early in July, as well for the

Flemish regional government, where the nationalist and the Christian democrats

have a strong majority together. Only then the negotiations for the federal

government will really start, or immediately get stucked in an impasse. The

Belgians who believe a new government will be in place before the summer are

rapidly diminishing in numbers.

Mr. De Wever

can easily live with this, and go along with his mission for a long time to

come. In the intellectual debate everything is going his way. Before the

elections he said more devolution was urgently needed as Belgium is composed of

two democracies, one dominated by the centre-right in Flanders, another one

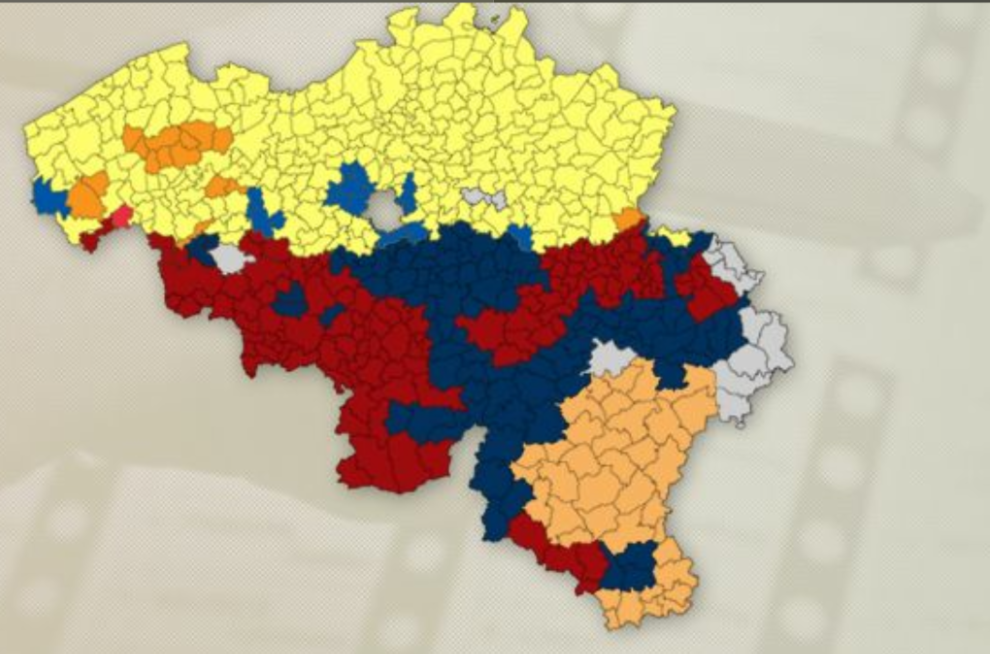

dominated by the centre-left in Wallonia and Brussels (see picture with the map of the biggest party in each electoral

district: yellow is the Flemish nationalists, red is the socialist, blue the

liberals, and orange the Christian democrats).

That is why he

proposed to form the regional government in Flanders first and as soon as

possible to prepare for the struggle for the federal government. In De Wevers

words it was time to change a quarter of a century of uninterrupted centre-left

rule in Belgium to a government prepared to consider the real needs of

Flanders. For such talk he was again condemned almost unanimously by the

Frenchs-speaking parties and media as the veiled separatist they always have

seen in him.

Immediately

after the election both king Philipp and the Flemish Christian Democrats and

liberals urged De Wever, as winner of the election, to forget that scenario and

to form the federal government first. The nationalist leader complied, only to

be taken in speed by Mr. di Rupo himself and his PS, who after only ten days decided

to form their regional coalitions first.

Since then the

battle over the perception of the new federal government – centre-right and so good

for Flanders, or centre-left, and a victory for French-speaking Belgium – is

well under way. A simple solution is not in the cards, not even the coalition

of the three traditional parties that made up the outgoing government, because

this was denounced as being centre-left by De Wever and his party, with

success.

What remains is

a new institutional reform , to adapt to the new realities, and make some quite

inventive solutions – why not a proportional all-partygovernment in the Swiss

way – possible. If this is not possible immediately,

it should happen somewhere in the next years. Mr. De Wever does not even have

to propose further measures for devolution. They have, in deeds if not in

words, been put on the table by his strongest opponents. And there is no way to

get them away there again.

No comments:

Post a Comment